The cool morning air wears a cloak of mist that hangs low from the dense canopy of the Malabar forest. We walk through a narrow patch of woods nestled between vast tea plantations, where the meandering path leads to a scattered cluster of huts whose guard dogs don't seem too pleased with our arrival. The cacophony of dog barks brings out the residents from their huts with inquisitive and apprehensive looks that turn to nervous smiles when we wave and greet them with a synchronised, "namaskaram."

We are here to see Vellan, whose dwelling can be found along the path that curves around the trunk of an enormous Peepal tree whose base has been meticulously swept clean. Beyond the clearing the path forks off onto a smaller trail which leads up to a hut with a wild garden, bursting with lush greens and fresh produce of the season. Almost identical to the other huts in the settlement, the bamboo and jack-wood structure sits roughly two feet off the forest floor on an earthen plinth made with a mixture of compacted mud, shell lime, and cow dung. A blue tarpaulin sheet is draped for roofing, a white and orange one for the walls. This modern practice is one of convenience - the traditional straw thatch roof and walls rely on a grass that only grows in certain marshy areas a long trek away. "I like the way our old homes looked - this blue is too bright. But it gets the job done easily," Vellan says, laughing.

The path leading to Vellan's home in the Malabar Forest of Southern India (left) and a short break to enjoy the view while foraging (right).

Vellan is a Naati Vaidyar, or traditional physician, belonging to the Kattunayakan tribe. The Kattunayakans - which translates to 'kings of the forest,' are one of the five ancient tribes of Southern India. Though they live predominantly in the rainforests of Kerala, small clusters of the tribe are spread along the Western Ghats of Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Andhra Pradesh. Kattunayakans are a hunter-gatherer community who once lived entirely off the forest produce they collected. Today, the government is systematically relocating them, their traditional practices slowly being lost to the convenience of modern living.

Vellan is lean with an able and strong physique. His eyes are aged with wrinkles of time, his gaze is piercing, and a few matted dreadlocks remain at the back of his mostly bald head. He speaks softly but with authority. His laugh is hoarse, like the call of a barking deer. His partner, Lakshmi, wears a broad smile. Her fingers are worn with age, but her nimble hands use a knife with artistic dexterity. She is fit and has the energy of a foraging bee.

'Vaidyar,' as Vellan is respectfully called, is attending to a patient. The man's wife and daughter are seated outside waiting when we walk up the red laterite steps leading to their front yard. The patient is suffering from a severe case of accumulation of uric acid in his joints, commonly known as gout. His wife tells us he wasn't able to walk or stand on his own for over two years and had to be carried up to Vellan's hut when they first visited a month ago.

Vellan is a Naati Vaidyar, or traditional physician, belonging to the Kattunayakan tribe.

"He now walks and even goes to work by himself. All this after just three sessions," she says with folded hands, a gesture of gratitude for Vellan. "We spent over six thousand rupees in hospital bills, but they could not cure him, and vaidyar has done miracles with his naati vaidyam." she adds. The daughter tells us how the "chemical medicines" made her father drowsy and nauseous and didn't alleviate his pain or discomfort. Vellan can be seen massaging the man's legs, back and arms using the medicinal oils he and Lakshmi prepare inside their home. The man winces as Vellan draws long strokes down his legs, squeezing the blood towards the feet to promote circulation. As Vellan tells us how his patient's legs were swollen to more than twice normal size, he talks about the balance within the body that needs to be maintained. As the man prepares to depart with his family, Vellan sends him away with a small bundle of dried pomegranate peel, which must be ground to a paste with water, rolled into small pellets, and taken twice a day.

Lakshmi leads us into their hut, lit blue with the sun streaming in through the tarpaulin roof, where smoke wafts from a small wood fire in the kitchen stove. To prepare the oil used to relieve muscle and joint pain, she starts by heating freshly pressed coconut oil in a large pot, adding a mixture of five forest herbs Vellan harvested the previous day. The herbs sizzle when they hit the hot oil, and she stirs the mixture until they turn dark and crisp. The crisp plant matter steeps in the cooling oil before it is crushed to release all the medicinal properties, then passed through a fine meshed sieve. A vibrant green, the oil is now ready to be applied to an aching body. Before we bid farewell, Lakshmi bottles the oil and hands it to us, saying, "It can even heal a broken bone!" Vellan invites us to tag along on a foraging excursion the following day.

We are giddy with excitement as we start the walk up the hill towards the wooded ridge in the forest of Mannikunnu Betta. Vellan leads us past massive Rosewood trees with trunks the girth of elephants, pointing out scratches on the bark as "the work of a bear." We ask if he fears encountering animals on his walks, and says not. "If I encounter a bear or elephant, I stand my ground and ask it to please let me pass. I wait till it walks off and then I go about my business," he explains calmly. "When I was young, my uncle taught me to identify the smells of animals. So when I walk I sniff the air to see if there is an animal nearby. If there is the smell of a big cat, I don't go deeper into the forest."

He was all of twelve years old when Vellan's uncle, the village vaidyar, taught him the ways of a Naati Vaidyar. He assisted his uncle in foraging trips deep into the forest, often spending the night on makeshift platforms atop trees. His uncle shared the secrets of their ancestors and passed down to him the art of healing with the help of the forest. Vellan stops to pick the heart shaped leaves of the Wadar manjal plant, which he says is good for skin ailments. "A simple paste of this leaf will clear the skin of pimples in no time," he assures us.

These days money has made things complicated.

We hike higher up the hill, pausing at every clearing to take in the view and snack on some of the delicious bananas from Vellan's garden. We stop at a rocky outcrop where we can see the entire stretch of forest and the towns that flank it. From here, it's easy to see how the tribals were squeezed out of their ancient homes. When asked whether he prefers living in a patch of wooded land on the fringe of estates and towns, or in the forest like his ancestors, Vellan says, "The old days were much nicer. There were no worries. Life was simpler. We only needed to take what little we needed from the forest to survive. These days money has made things complicated."

Vellan walks swiftly through the old growth of the forest with silent footsteps like the padded feet of the leopard. He stops next to a tree with a thick, rough bark and scrapes some off using his machete. "This is Jeeva Vriksham," the tree of life. "It can give you energy and power," he says, stuffing the bark into his satchel. Just next to the tree is a small cluster of grass which Vellan points at and says, "This is Atthi grass, it can be used for abortion, but we don't need that now," before walking on.

At the summit we sit down to eat more bananas and some biscuits as we survey the beauty of the valley around us. Vellan tells stories of how his uncle cured broken bones and severe illnesses with the medicine from the forests. "But the old ways are vanishing. I don't have children, so my practice will die with me," he concludes, sounding wistful.

The making of traditional medicine: (left) oil bubbles as it absorbs nutrients from the herbs, and (right) the fully steeped mixture before it is strained and bottled for pain relief.

At the tribal settlements we visited, most homes had lovely kitchen gardens growing lush with staple produce such as cheera (a type of leafy plant that has purple leaves and stalks), winged beans, and colocasia (wild yam), whose leaves and root tuber are used extensively in local cuisine. They also grow spices and herbs such as turmeric, ginger, chilies, tulsi (holy basil) and bay leaf, among others. The common practice is to cook rice and pair it with a leafy green that is in season, or a starchy root tuber growing abundantly. These meals reflect the prevailing season, a harmony that allowed tribes to thrive in the forests.

The crabs have little meat, but they are succulent and sweet.

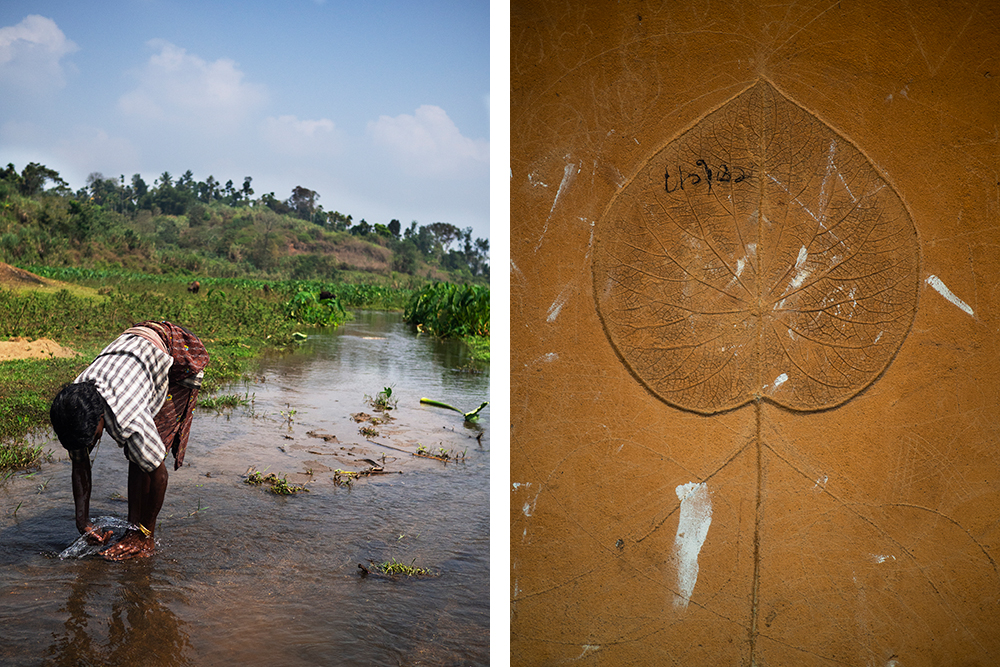

During one visit, we hear of a mud crab that is considered a delicacy - some even believe it has medicinal properties to soothe body pain. Shantha and her sister, Usha, of the Panniya tribe, graciously allow us to join them on a dig in the river banks and marshy fields. The Paniyas are a nomadic hunter-gatherer sect that are known as prolific honey-gatherers. The sisters currently live on a government relocation site housing around thirty families. Here, they are provided with housing, water, electricity and a small piece of land to farm. Most families in this settlement grow small patches of coffee, arecanut, cardamom and pepper. They say this isn't enough to live off of, but it adds to the wages they earn from work as farm hands or labourers.

We walk down the steep steps that lead us to the banks of the river. The sun has peeked over the hills in the east and the day is quickly growing warm. We cross the river, which is more like a stream at this time of year. The floodplain on the far bank is growing thick with colocasia and amongst the marshy undergrowth we spot small crab burrows. The women quickly get to work, digging and shoving their arms shoulder-deep into the burrows to retrieve a small crab from each one. To prevent the crabs from escaping, they break off the pincers and legs and bundle them into the large colocasia leaves. In a little over an hour, we collect well over two kilos of crabs. The sisters look up at the steadily rising sun and decide it is time to go and collect firewood.

At the water's edge, we wash the mud off the crabs, and the women sort them out for the two houses. When we return, their mother has started chopping onions and tomatoes to cook the crab with. Departing with our own small portion of the crab catch, we are instructed to sauté onions, garlic, ginger and tomatoes with a healthy dose of turmeric, chili powder and black pepper. The crabs have little meat, but they are succulent and sweet.

After a few weeks walking the forests with Vellan, and watching Lakshmi, Shantha and Usha harvest their daily needs from what grows around them, I pray that these practices are not lost to the tides of time. Systematic modernisation of these tribal communities is influenced by a prevalent caste system that attaches stigma to tribal practices. Communities bearing the knowledge of an ancient art of sustainable living are being pushed to change and adapt to a world of money and vanishing forests. During the recent Covid-19 pandemic, these tribal communities relied on their knowledge of the forests and continued to procure the freshest of produce to feed themselves and their families. The few who keep these practices alive allow us the fortune of experiencing their ancient commune with the earth and its forests.

Note from the authors: This story was made possible through the assistance of our translator and guide, Shivakumar, a resident of Wayanad who works as an estate manager.

To learn more about the tribes of Wayanad and their history:

Paniya People of Wayanad: A Brief Ethnography by Vasundhara Krishnan

Tribals in Kerala from the Kerala Institute for Research Training & Development

What Happened in Wayanad by A. Damodaran

The Unseen Indians: Fading Tribal Population of Wayanad by Kuvalayamala

Land Alienation and Livelihood Problems of Scheduled Tribes in Kerala by Dr. Haseena V.A.

For more on organizations that work with the tribes of Wayanad:

Tribal Unity for Development Initiatives

Nilgiris Wynaad Tribal Welfare Society

The Highrange Rural Development Society

People's Action for Educational and Economic Development of Tribal People (PEEP)

Adhwaith is a trained pilot and adventure athlete with a passion for wildlife and forest conservation. Follow his adventures on Instagram @stonemonkee.

Azra Sadr is a photographer based in India who shares her love for food and travel through photography. For her commissioned and personal projects, visit azrasadr.com and follow her travel experiences and photo stories @azrasadr.