He's remarkably steady. Even 6 hours into harvesting tomatoes. Even as we discuss his recent divorce. Even as we discuss the government seizing his family land, Roy Mitchell has an enviable calm about him, like the tide rolling in so smoothly you don't even notice how hard it's been working all day. Despite his calm demeanor, Mitchell is not unengaged - far from it. He employs twists and turns of phrase, from gentle chuckles to emphatic mhmms that serve as fleeting windows into a hard working man who's navigated a challenging life, doing what he can to make it all work.

He's in a work program that, while undeniably beneficial for him, places him in a vulnerable position.

Mitchell was born into a farming family in central Jamaica, one of seven siblings. The times were hard, but his father grew much of the food the family ate - yam, cassava, banana, pineapple, goats, chickens, and a milking cow that was also used for draft labor. From an early age, Mitchell loved farming. He got to work alongside his father, who was born and raised on that same piece of land.

His father was a notoriously quiet man and exceptionally hard worker. He only spoke when necessary, and if Mitchell was doing something wrong, his father would gently correct him and keep on working. His dad would live to be ninety-seven years old. When he was ninety-four, Mitchell's mother, fifteen years his father's junior, would hide his machete to try and keep him from working. Rather than sit down and relax, he'd walk the three miles to the nearest town to buy a new one and keep on working.

Mitchell's mother, fifteen years his father's junior, would hide his machete to try and keep him from working.

Maybe this is where Mitchell gets his iron work ethic from. Or maybe it's because he's been farming since he was twelve years old, at first alongside his father, and now on his own for the last eight years, since his father's passing. Or maybe it's because he's in a work program that, while undeniably beneficial for him, places him in a vulnerable position.

Roy Mitchell, a migrant worker from Jamaica, employs a steady hand harvesting tomatoes in New Hampshire.

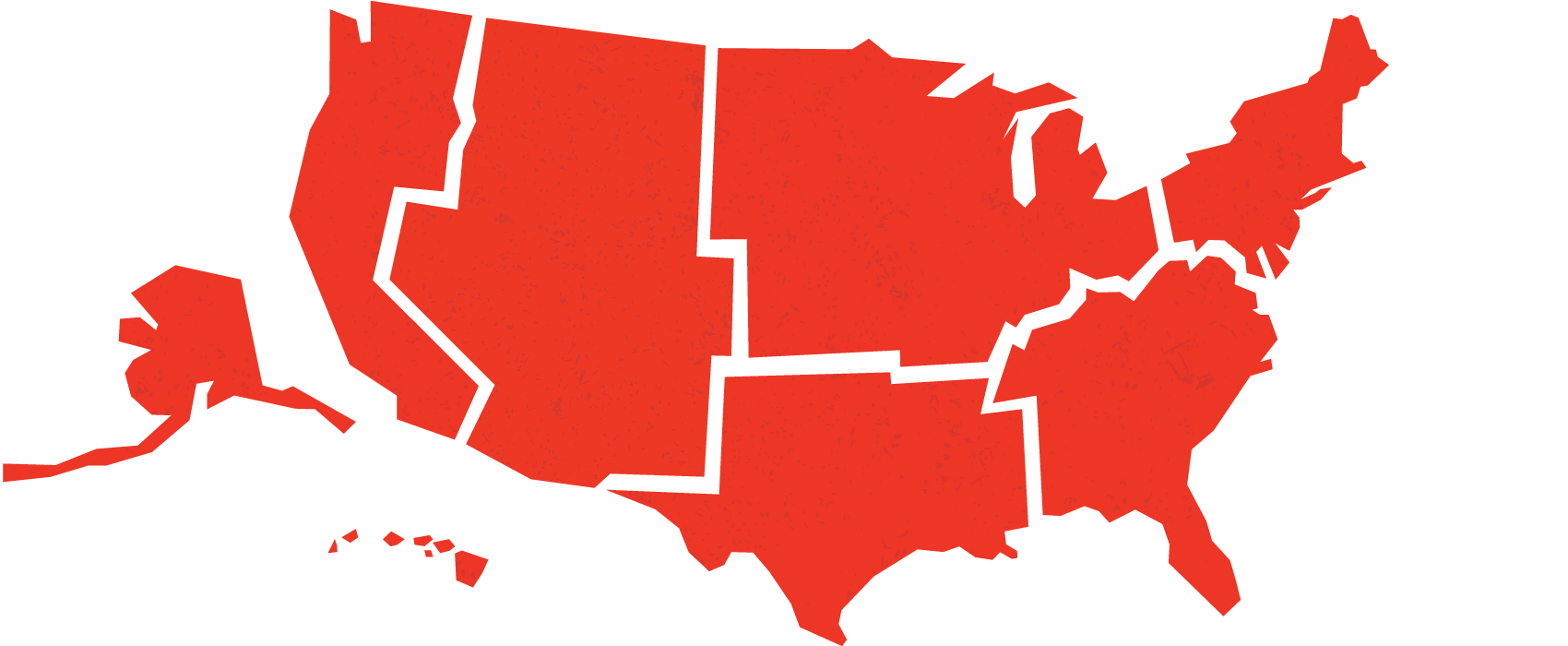

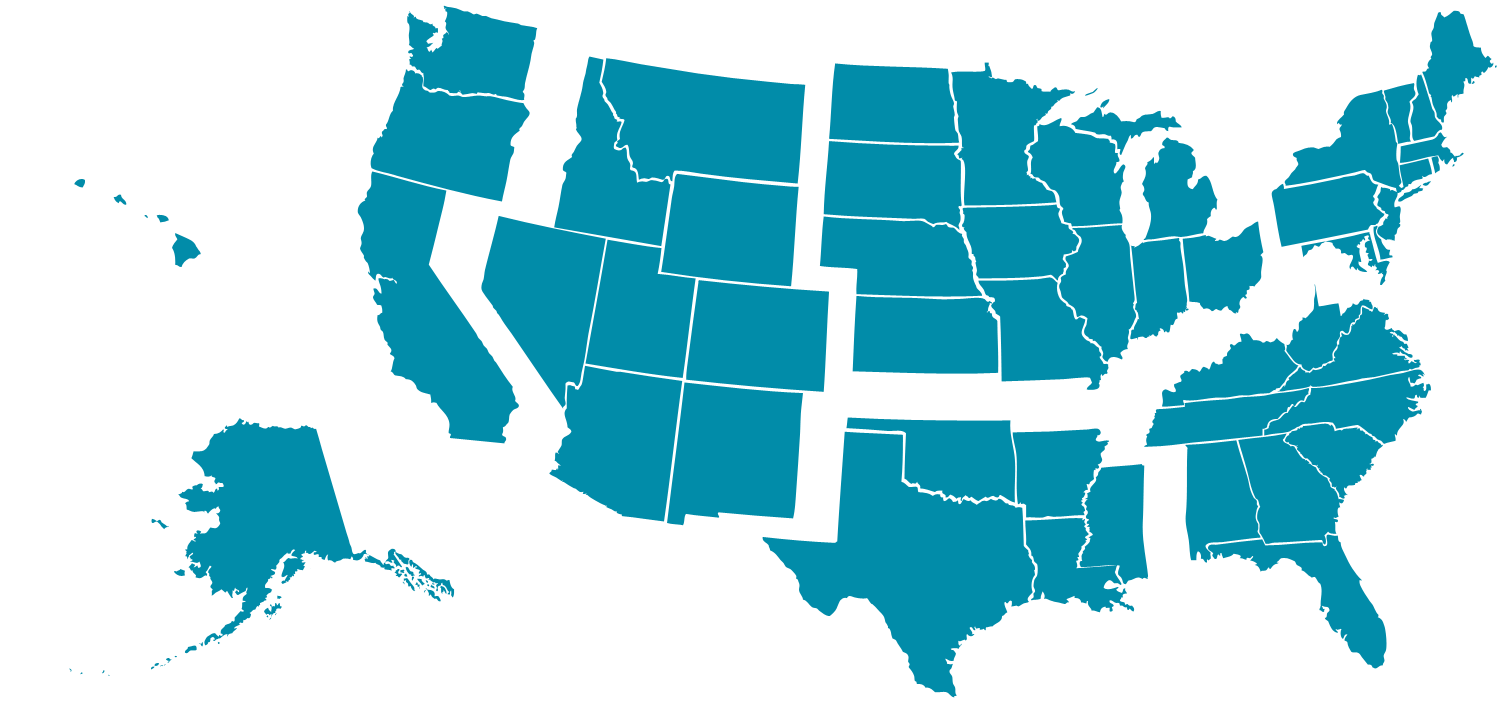

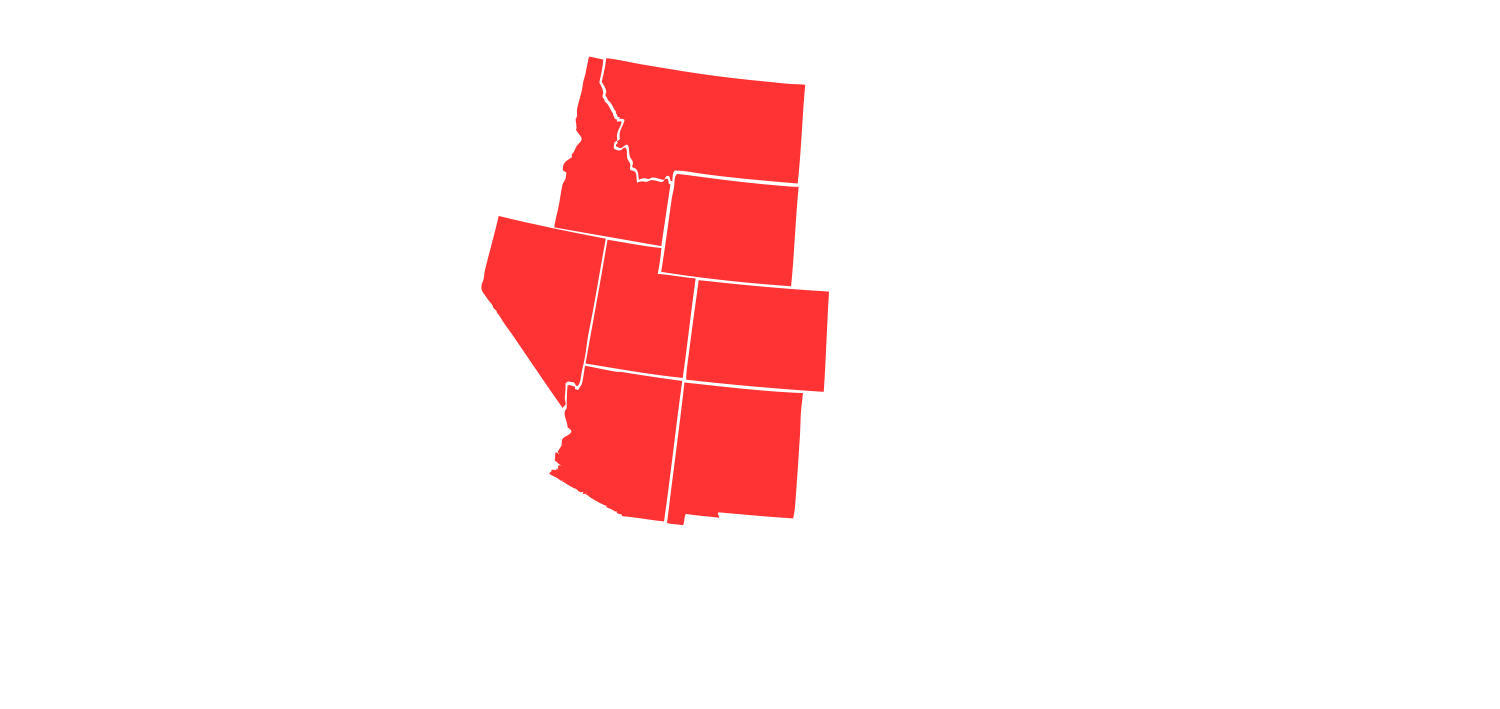

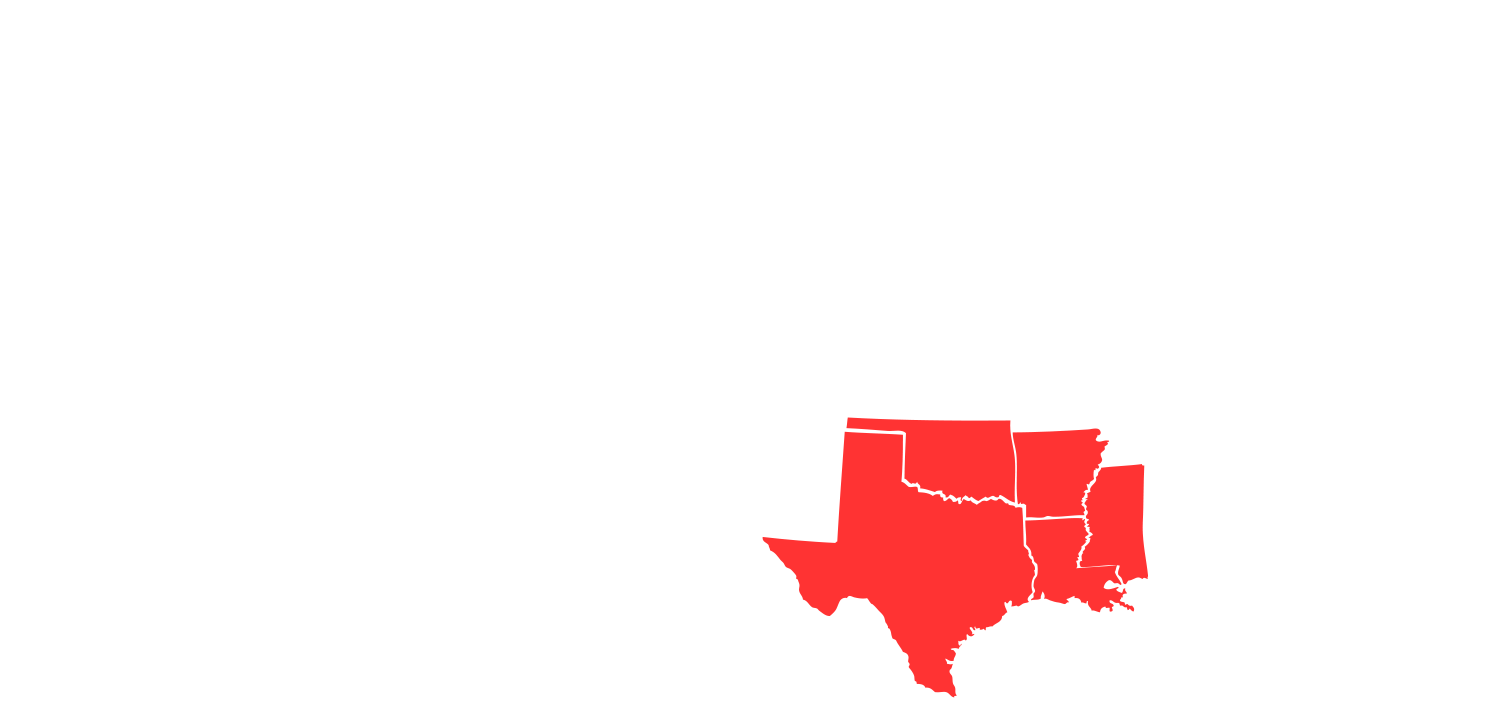

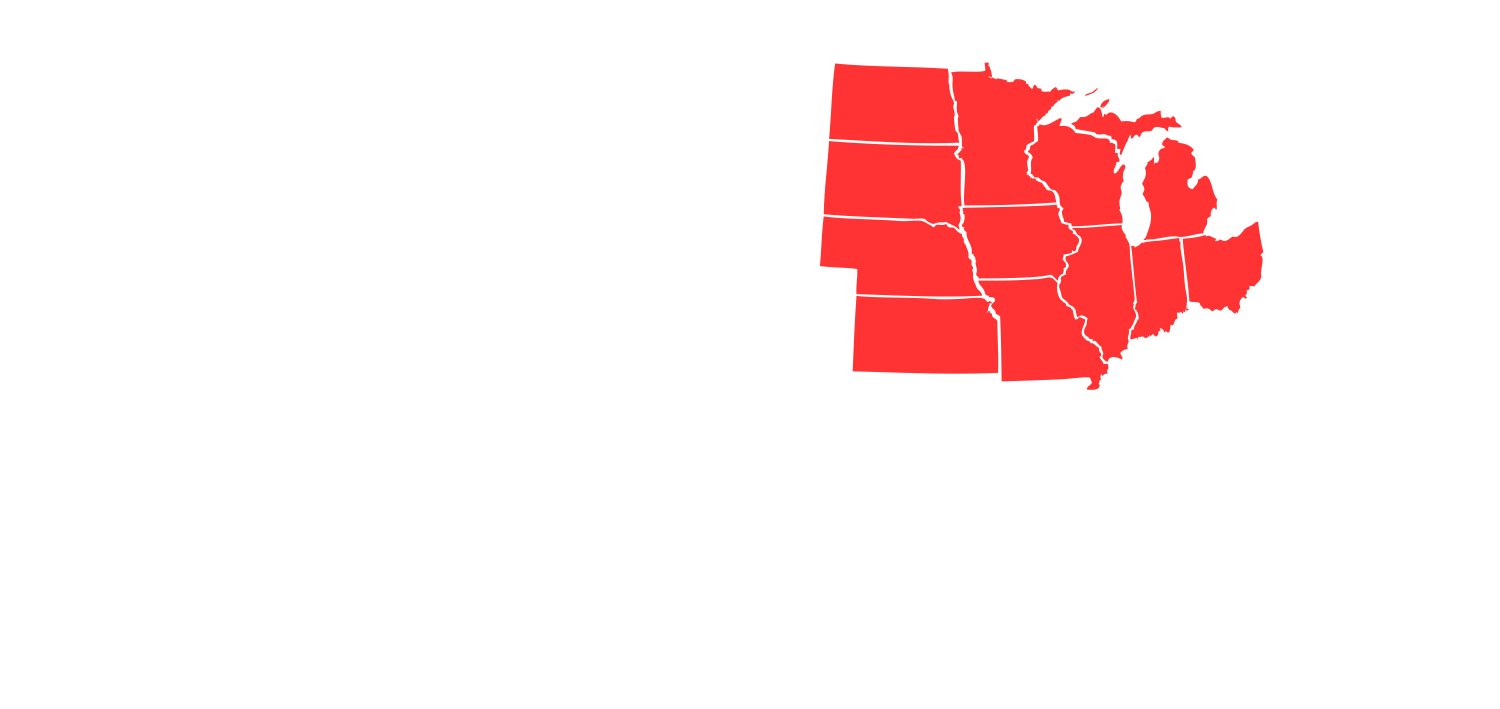

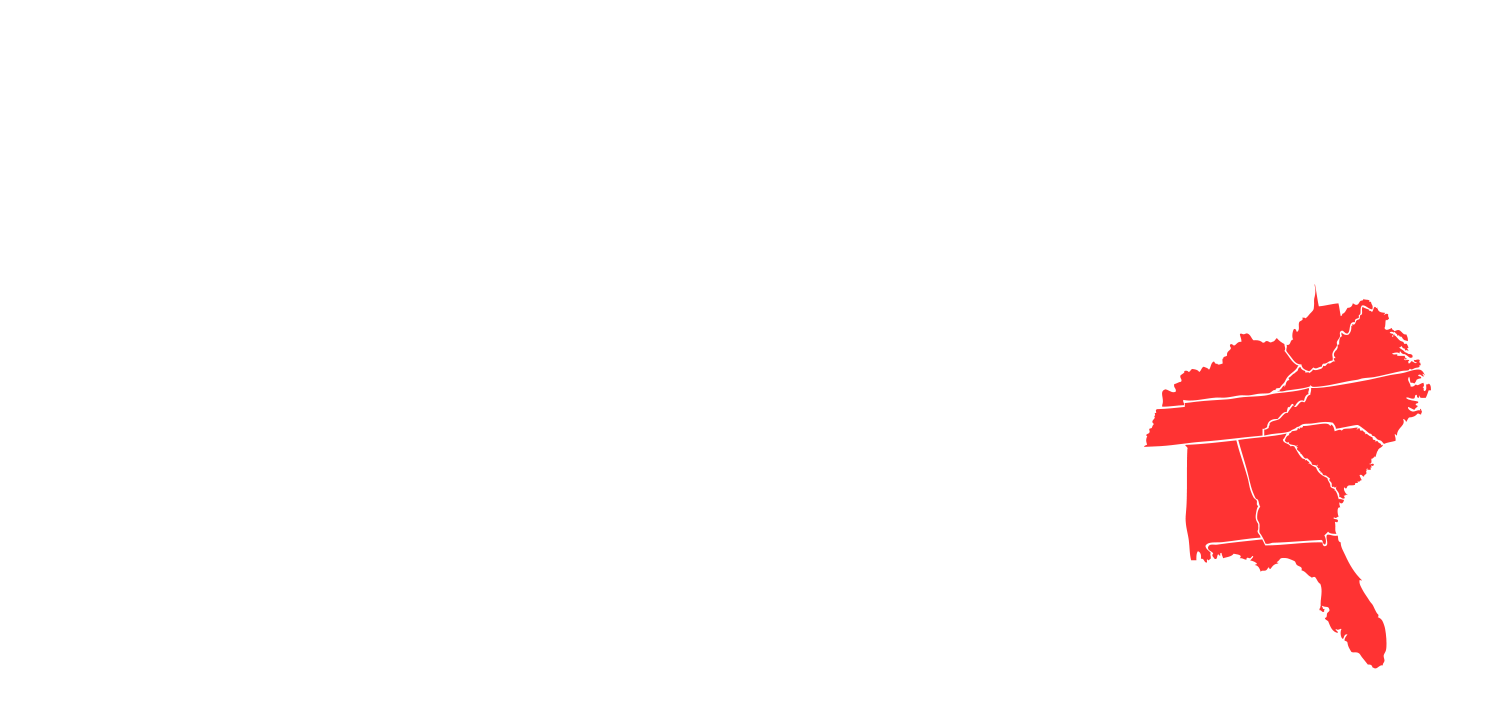

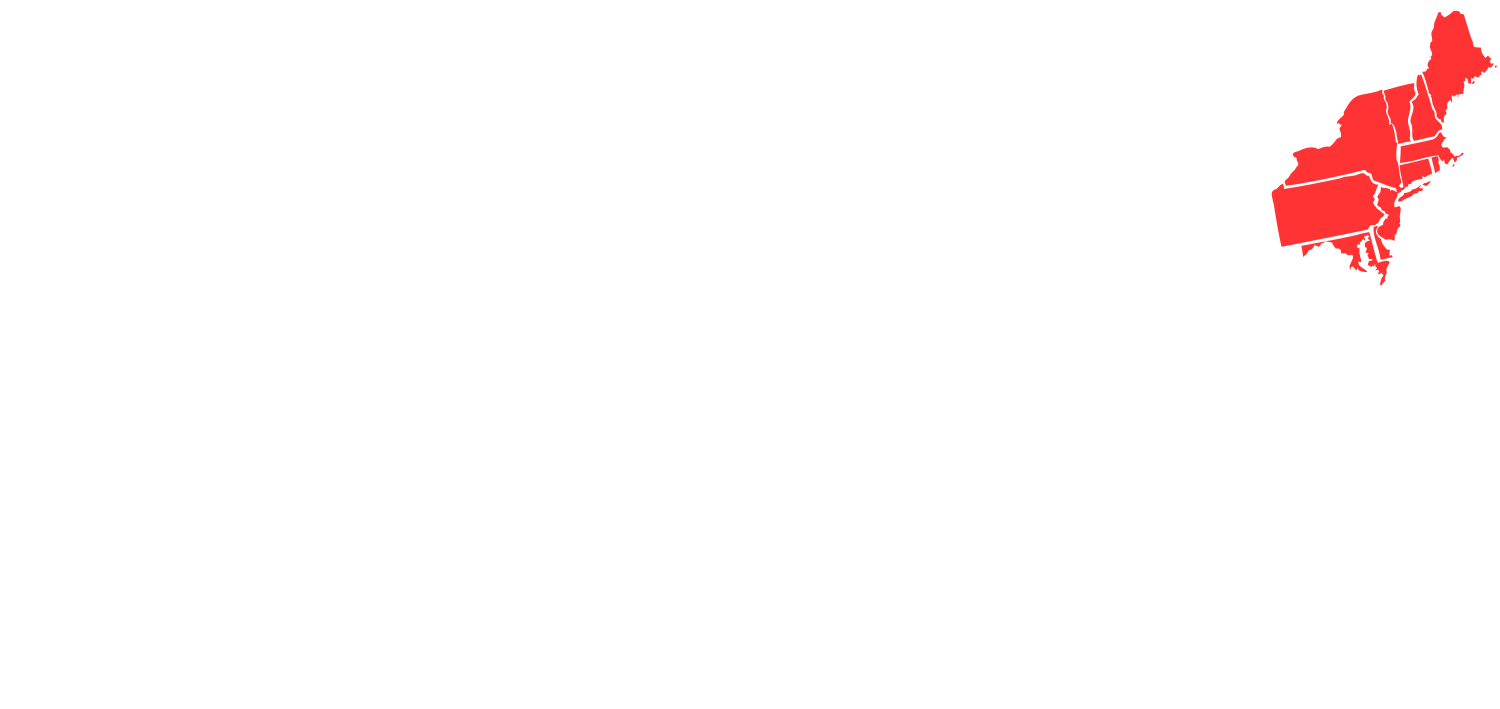

Mitchell has been coming to the United States on temporary work visas for almost thirty years. He started out cutting sugarcane in Florida, moving up to tobacco in Virginia, then to apples in western New York, before landing at an orchard in the Upper Valley of New Hampshire, and finally moving to vegetables, down the road at Edgewater Farm, where he has been for almost twenty years now.

You never know what you're going to get when moving to a new farm.

You never know what you're going to get when moving to a new farm; some bosses are nice, some are not. He's had a few bad experiences with abusive bosses, who treated Mitchell and his contemporaries with demeaning language, long hours and repetitive work. This is, unfortunately, not unexpected territory for a dark skinned, foreign-born man in America. When he leaves the farm, with or without his buddies, he says they go about their business, keep their heads down, and wave back if someone engages. While everyone in his current home is cordial, you just never know.

Mitchell feels fortunate to have found Anna and Pooh, owners of Edgewater Farm. He says they are like parents, true family. They care about him. They helped him organize a fundraiser when his home was destroyed in a hurricane a few years back. Their kids now help run the farm, and Mitchell lives with their son, Ray, his wife, Jenny and their three-year-old son, Hobbs, with whom he shares jokes and corn on the cob, sometimes even babysitting when the need arises.

Despite having found family in the Edgewater crew, Mitchell leaves his family behind in Jamaica for six months out of every year. His four daughters and three grandkids live in the small town where he was raised. He still operates his own farm while he is away, corresponding with a crew over the phone every few days to coordinate field work or harvest as necessary. So what makes it worthwhile for him to spend so much time working in the U.S. each year?

With a smile cracking the corners of his mouth, Mitchell tells me that in order to make as much money as he does in the U.S., he'd have to be a politician or a drug dealer back at home. His taxes are high, his bills are expensive, and his lease keeps increasing every year. His family owned their property for the first few generations they farmed it, but an uncle sold it to the Jamaican government many years ago, and he now leases it from them.

Trees planted by his father and grandfather, some of which are more than one hundred years old, will be cut down.

The Jamaican government not only raises his rent every year, they are also planning on building a new highway that will run right through his family farm. They plan to raze the land and knock down both his and his parents' houses, which currently stand just a few hundred feet away from each other. Trees planted by his father and grandfather, some of which are more than one hundred years old, will be cut down.

Mitchell says that the government has offered to provide him with a new piece of land, build him a new house, and move his parents. I did a double take, my eyes wide, and Mitchell confirmed that yes, they will relocate his dead and buried parents to this new piece of land. He knows people who have already been displaced, and are still awaiting relocation after six years. With his livelihood and family history on the precipice of destruction, Mitchell feels frustrated and powerless, like there is less and less to go back to at the end of the season.

Over the last twenty years, New Hampshire has come to feel like home. Except for the snow. Mitchell does not like snow. He socializes with many other Jamaican men and women on his days off, some of the more than two thousand individuals employed on H2-A and H2-B visas in Vermont and New Hampshire(USDL). If his situation were simpler, he says, he would move here, where there are greater opportunities for employment, education and success. But he can't stay for more than a few months each year. His visa is temporary. He could embark upon the desiccated marathon road of green card application, but is far from sure that the process would result in granting him residence.

Mitchell pays federal income tax, but doesn't receive any benefits of living or working in the U.S. He has worked faithfully for the last thirty years, serving American businesses, and despite his desires, he'll be heading back home to Jamaica at the end of this, and every foreseeable, season.

Mitchell pays federal income tax, but doesn't receive any benefits of living or working in the U.S.

With a cocktail of hardships swirling somewhere between his heart and head, Mitchell remains content to work steadily down the row of tomatoes. Sometimes standing, sometimes bent, sometimes sitting. Occasionally he'll talk with the other crew members. But mostly, he just works quietly, filling tote after tote with tomatoes.

Andrew Plotsky is the principal of Farmrun, an agrarian creative studio that specializes in branding and photography. He lives in central Vermont, where he and his wife, Rita co-operate Stitchdown Farm, a diversified flower farm and floristry. Follow him on instagram @aplotsky