In 2010, Rev. Dr. Heber Brown III, of Baltimore, Maryland's Pleasant Hope Baptist church, was visiting members of his congregation in the hospital, where they were being treated for diet-related health problems.

"Seminary trained me to give a scripture and pray for people in the hospital, but I wanted to do more," says Brown. He longed for a way to more fully address the physical needs of his congregation, to create a place where the congregation and community could reconnect with the land and food, akin to the relationship their elders had. He pictured the front yard of the church as a 1500-square-foot garden.

When he brought the idea to his congregation, women and men, both young and old, stepped up to bring the vision to fruition. While Brown initially expected the project to spark a young adult revolution, his elder members turned out to be the most faithful work crew.

While Brown initially expected the project to spark a young adult revolution, his elder members turned out to be the most faithful work crew.

"A lot of people might be tempted to believe that all this craze around local and organic and foodie culture is new...There is nothing new about this at all," says Brown. "The [elder members] were the ones retired, with time on their hands, fresh memories from their childhood, resources and information about gardening. They were the ones who made the difference here."

Within a few years, the plot provided over a thousand pounds of produce to the local community each growing season. Meanwhile, Brown fostered even bigger dreams. He imagined a network of churches that could transform the lives of black farmers and eaters alike: an alternative food system led by those most directly affected by food inequity and food insecurity. Or, in Brown's words, "food apartheid"-the policies and planning decisions that construct communities in such a way that they are distanced from fresh food sources.

"Communities struggle not just with access to healthy food," he says, "but because they don't have control of their food system."

He wanted pastors, churches, and communities to consider the role faith congregations could play in crafting a response to this challenge.

"Churches are one of the original anchor institutions of society," says Brown. "Churches, especially in the black community, have anchored us in ways that no other institution to this day has been able to do."

At noon on the first Sunday of each month, a farmers' market is held at Pleasant Hope Baptist Church, featuring locally grown and canned goodies from BCFSN members.

After centuries of violence, including targeted attacks by the KKK, buildings burned by racist terrorists, and pastors murdered in their pulpits, the black church-a phrase used to identify historically African American denominations that share qualities and cultural connections-continues to come back stronger than before. It also remains one of the largest land-owning entities in black communities.

The black church-a phrase used to identify historically African American denominations that share qualities and cultural connections-remains one of the largest land-owning entities in black communities.

What institution is better positioned, Brown thought, to impact not only spiritual health, but political, economic, and educational aims? "The black church has no rival in this country in addressing those issues," he says.

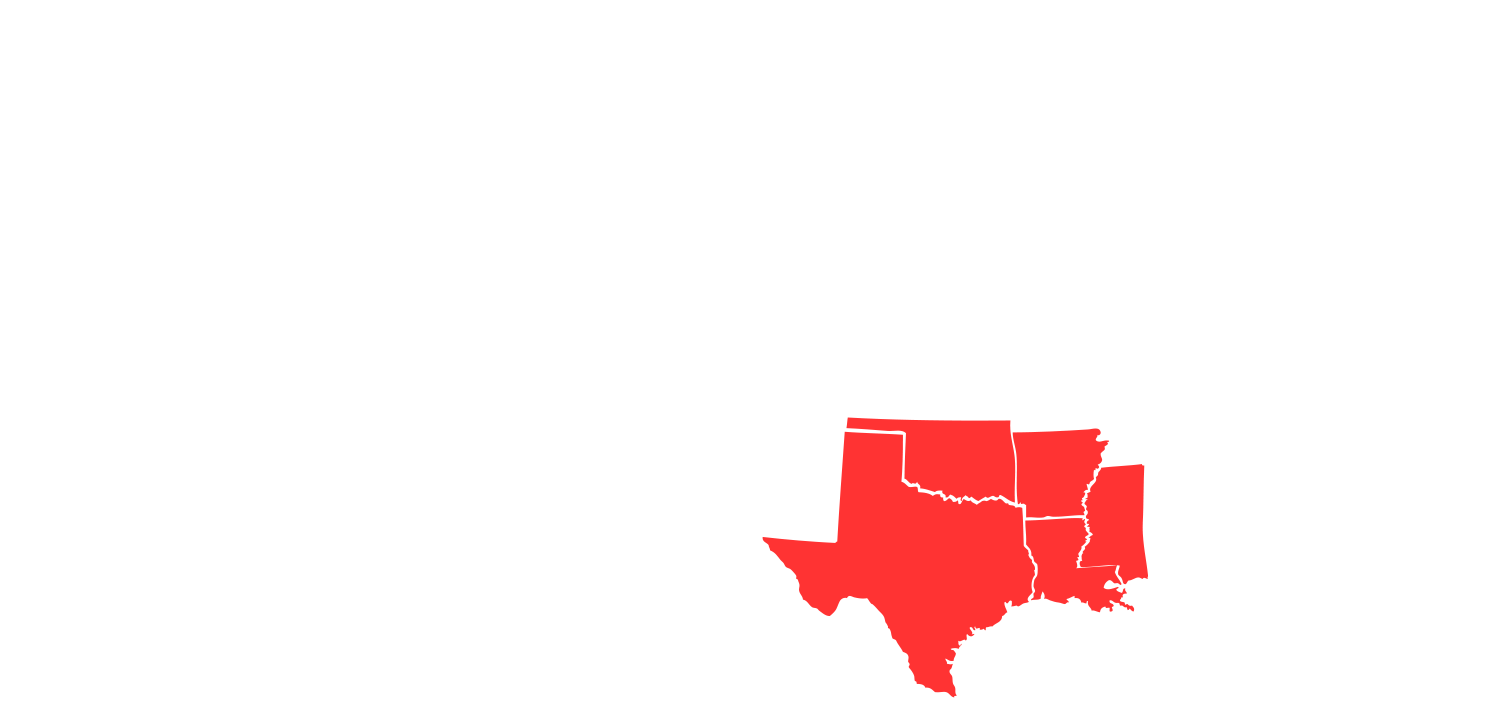

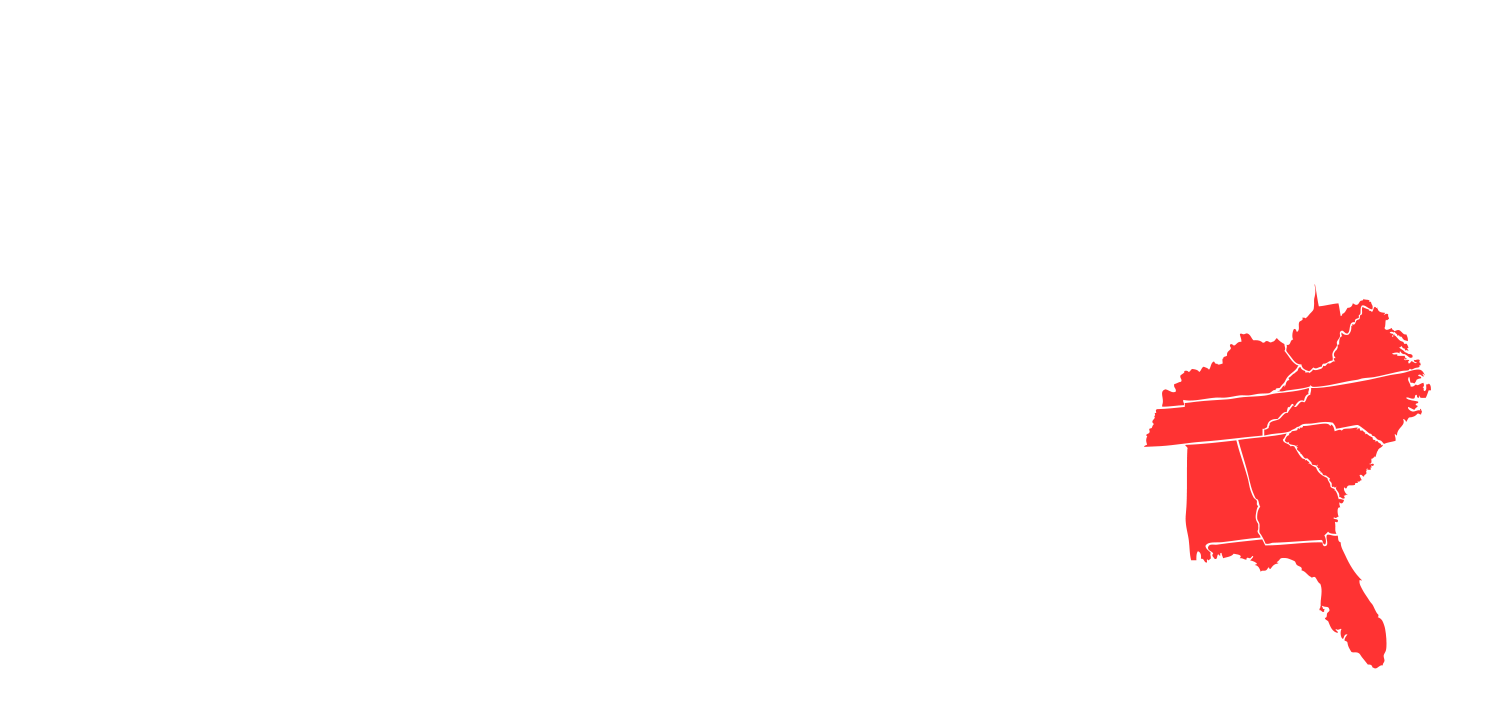

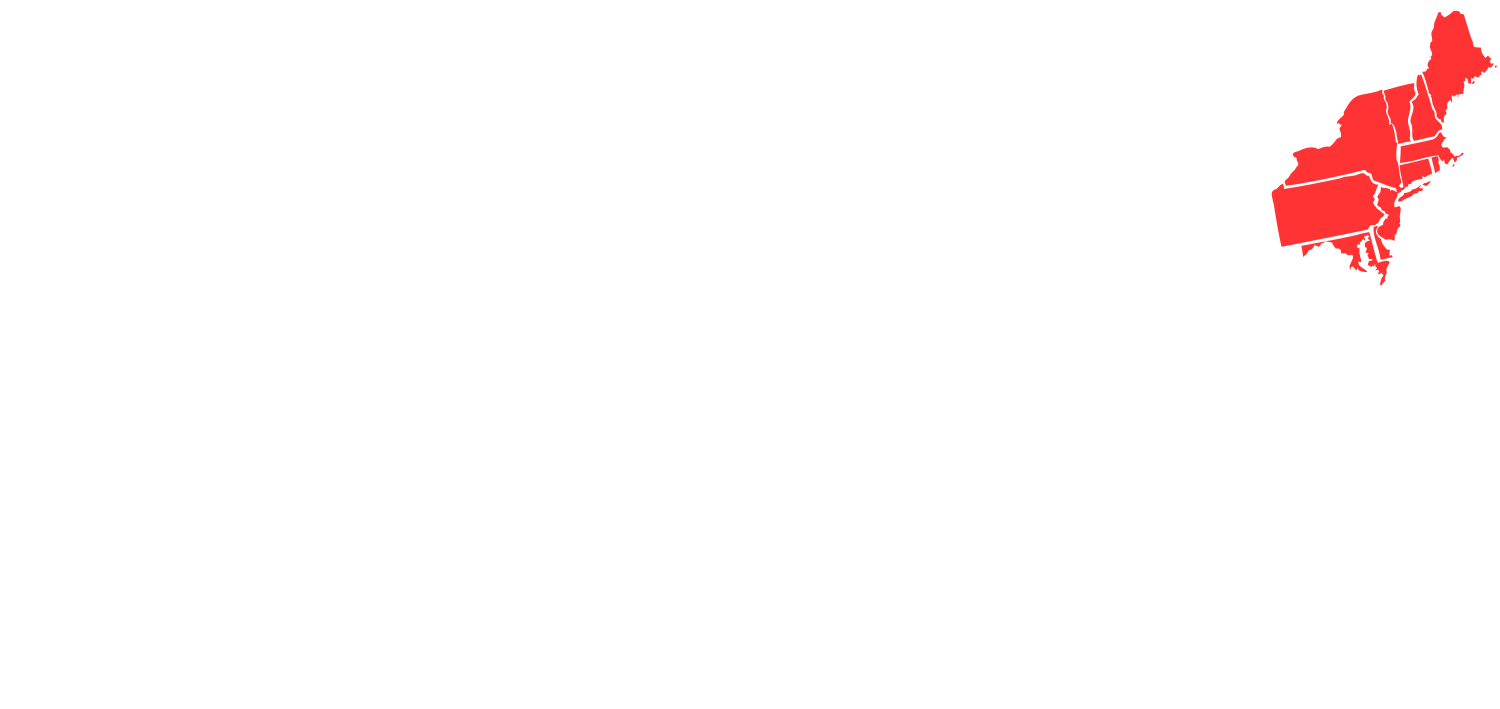

In January of 2015, Brown began sharing this vision with churches along the east coast. Just three months later, his city rose up in protest against the death of Freddie Gray at the hands of Baltimore police. In the bosom of the uprising, in response to years of abuse by those entrusted to protect and to serve, the Black Church Food Security Network was inadvertently born.

"We were getting calls here at the church from communities that were hungry. The corner store they depended on was closed. The school system was closed a few days, and so school lunches that children were dependent on were not available. Public transportation shut down a day or two, even the buses and subways...When city services backed up off the black community, I saw an opportunity for the church to lean in."

He called one farmer friend, who reached out to her other farmer friends, and soon church vans full of food were driving north up I-95 to Baltimore.

"We transformed our multi-purpose room into a food distribution center, set up shop on street corners, and got food in the hands of people."

After two weeks of running their emergency network, Brown realized they were already implementing the idea he'd conceived just a few months before."We had a system. We had distribution, production, aggregation sites, all working together."

If we can do this for two weeks, Brown thought, we can do it for longer.

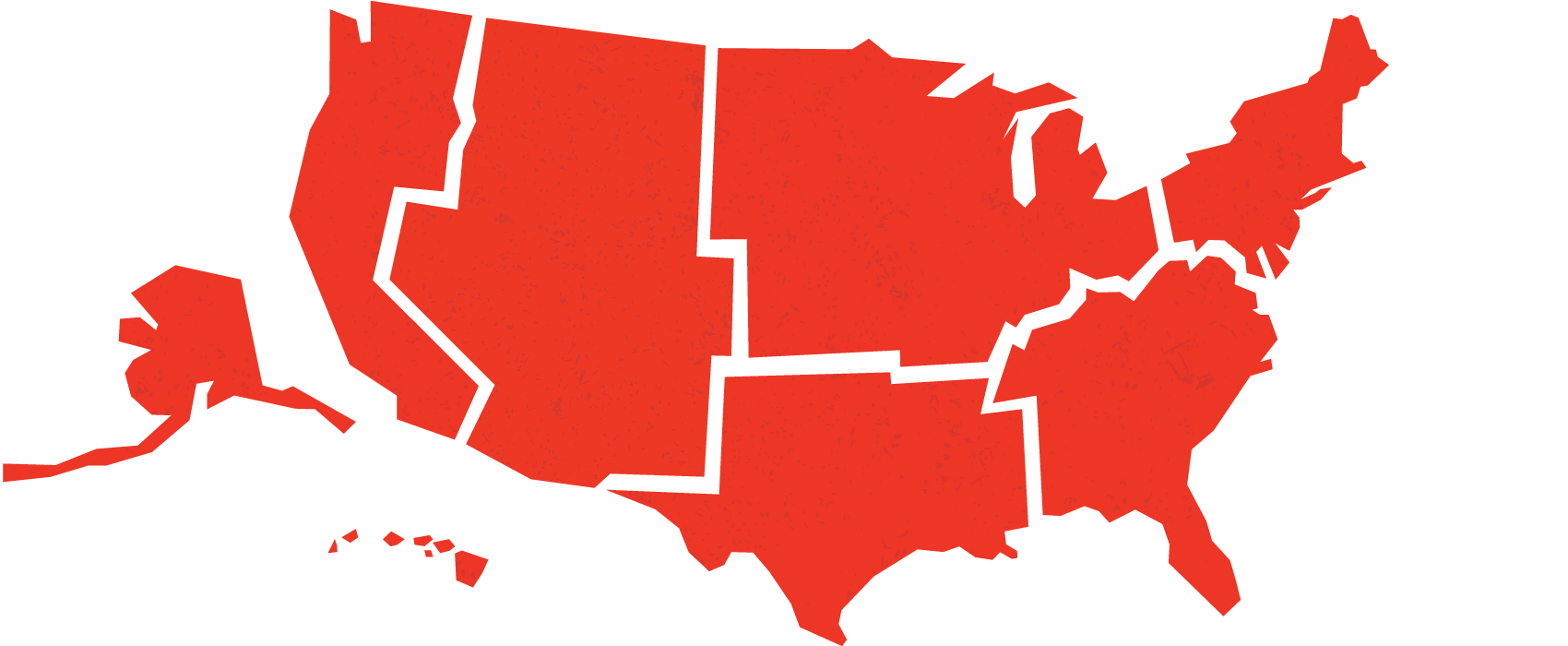

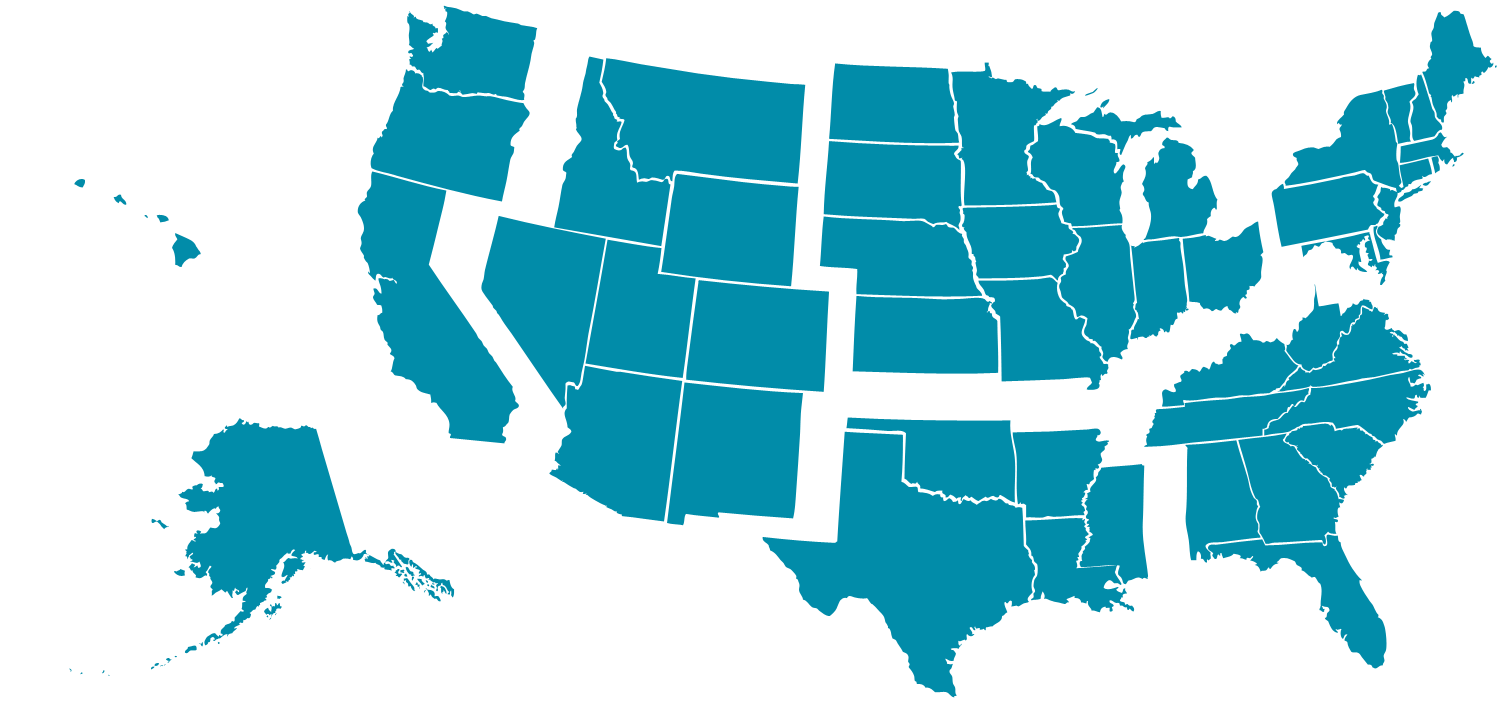

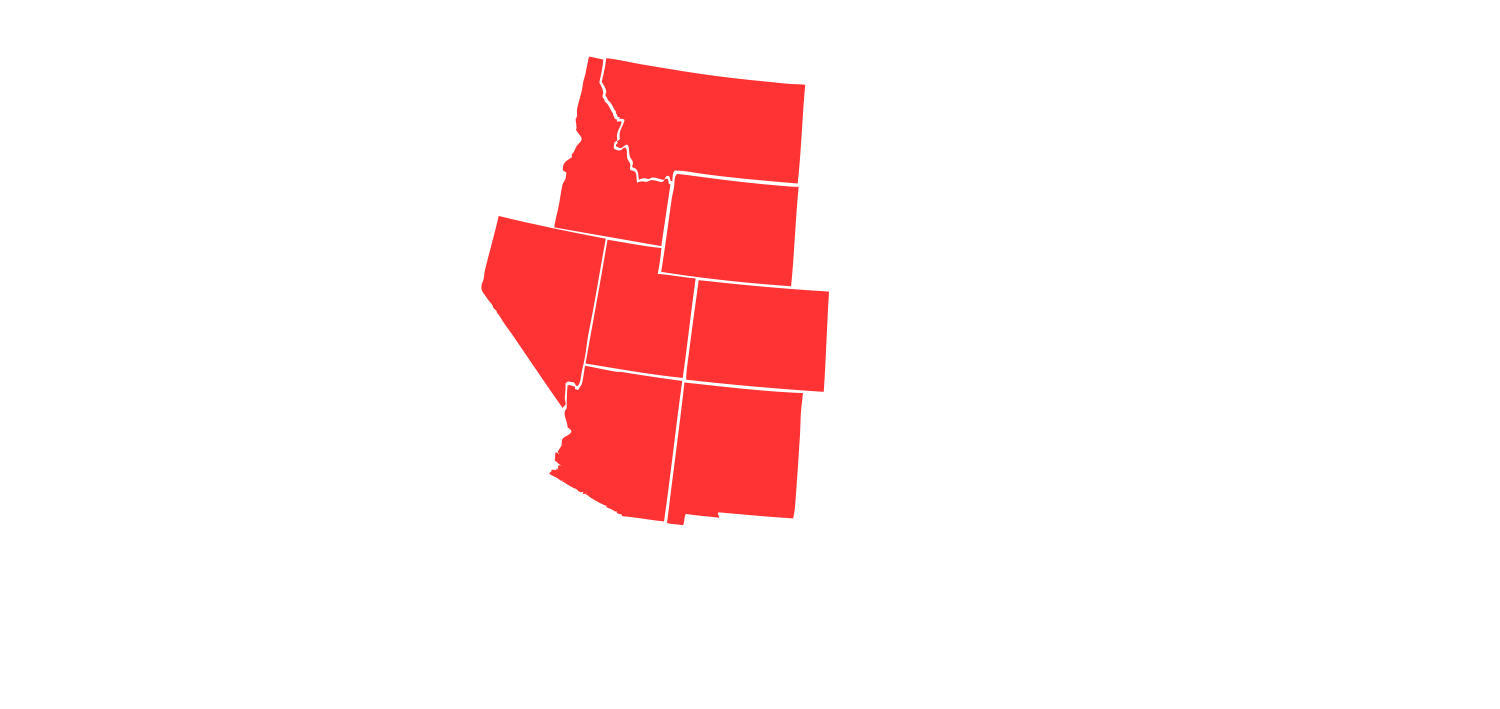

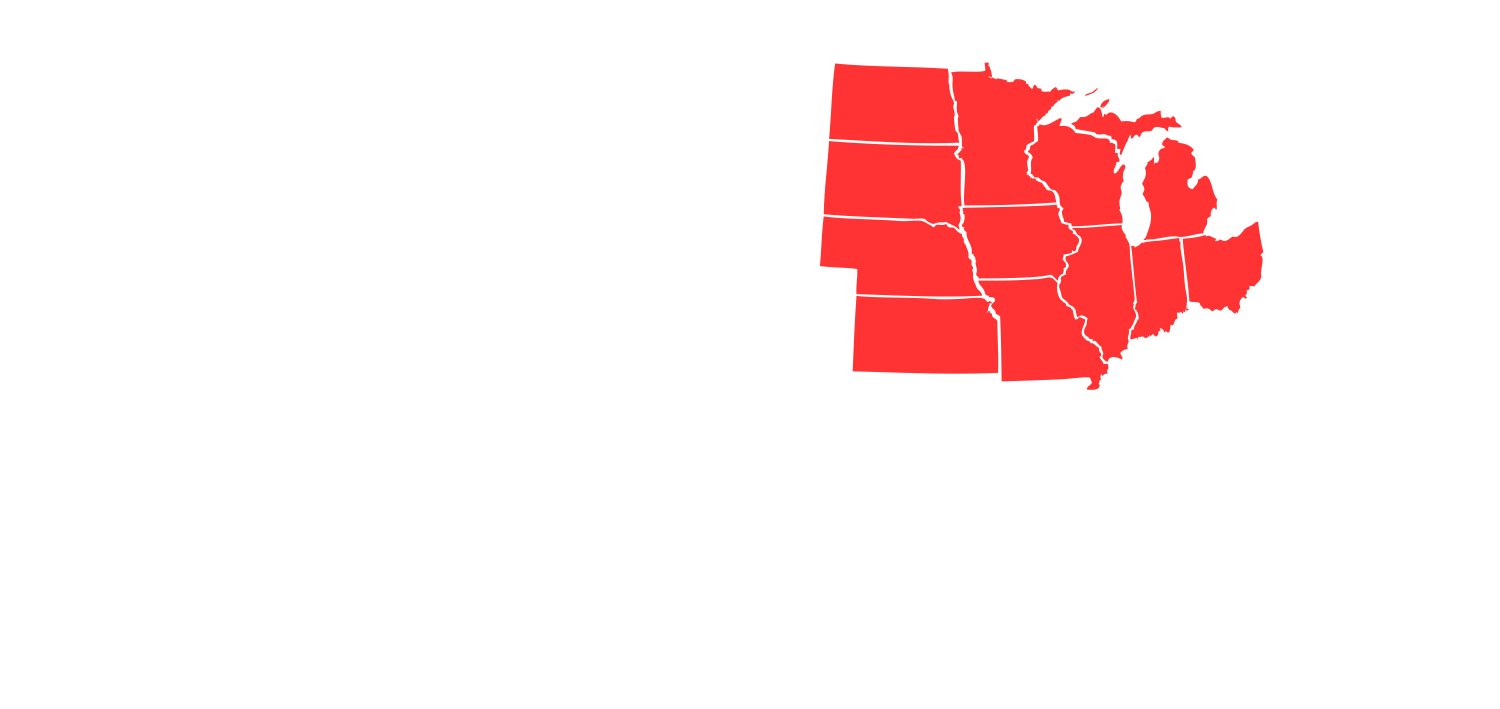

Right now, the Black Church Food Security Network consists of ten churches actively growing food on their land, with many more expressing interest in joining. They also run a pilot Soil to Sanctuary community market, pipelining produce from black farmers into Pleasant Hope to run a mini farmer's market. Many members of Brown's congregation already shop at high-end grocers; through the Soil to Sanctuary pipeline, Brown encourages them to refocus their money towards black farmers, providing higher payment than these farmers might otherwise command. Their goal is to set up similar markets across the country.

The network also encourages communities to contend with generational trauma associated with land and farming and properly direct their pain away from the land itself.

"It wasn't the land that enslaved African people," Brown says. "It wasn't cotton that cracked whips. It wasn't corn that lynched women and men. Land ownership and deep commitment to agriculture can be a pathway to freedom and empowerment for the African American community, not a source of our enslavement."

"Land ownership and deep commitment to agriculture can be a pathway to freedom and empowerment for the African American community, not a source of our enslavement."

Apart from a small amount of seed funding, the program is mostly self-sustaining. Autonomy and agency are central for Brown, and so the network is very selective with financial partnerships. Through the network, Brown aspires to see the black church supporting black community so that they need not rely on the government or nonprofits to step in. "There is a role that churches play that we should never turn over to a nonprofit to do for us, particularly given the challenges we face and given the power dynamics in which we engage," he says.

Brown and his community don't have the luxury of talking about farming in a purely therapeutic sense.

Brown and his community don't have the luxury of talking about farming in a purely therapeutic sense. "We won't have a place to live if we don't think about farming and land ownership and owning our food sources," he says. But through the ongoing work of the Black Church Food Security Network, Brown envisions an alternate food system that simultaneously heals historic trauma while paving a path forward, that addresses imminent physical needs while forming powerful communal bonds.

"If racism and white supremacy continue in this nation, and I've got a sneaky suspicion that [they] will," he says, "there will be a community here-a special and sacred circle-where black folk can come, lay their burdens down, cry, shout, sing, pray, preach...And plant. Harvest. Eat."

Kendall Vanderslice is a baker, and a writer on the intersection of food and faith. She is a graduate of Wheaton College (BA Anthropology) and Boston University (MLA Gastronomy) and a student at Duke Divinity School. She has written for Christianity Today, Religion News Service, Faith & Leadership, and Christ and Pop Culture. Her first book, We Will Feast: Rethinking Dinner, Worship, and the Community of God, comes out in May 2019 with Eerdman's Press. Find her on Twitter @kvslice.

LaSchelle Janey Ross is a 3rd generation photographer based in Maryland with a devotion to children's rights and family heritage. Her ongoing mission is to explore the limits of the camera and capture the natural spirit of family life and show the beauty of diversity in humanity. View more of her work at www.schellephotography.com.