Dr. Jennifer Gaddis arrives exactly two minutes late to our scheduled video-chat, apologizes, says, "I'm having a slow start to my morning. I have no excuse other than that," then tells me that her backyard chickens are adjusting to dropping temperatures in Madison, Wisconsin. I find everything about this instantly endearing.

Perhaps her candor and friendliness owe in part to the nature of virtual calls during the pandemic - when many of us are working at home and, therefore, have few excuses for tardiness and few occasions for socializing - but I sense that she is this way under any circumstances. These characteristics can be rare in the competitive and at-times esoteric world of academia; then again, Gaddis had not always imagined she would end up as an academic.

unless you have good mentors who are explaining unwritten stuff to you, it can be hard to figure out

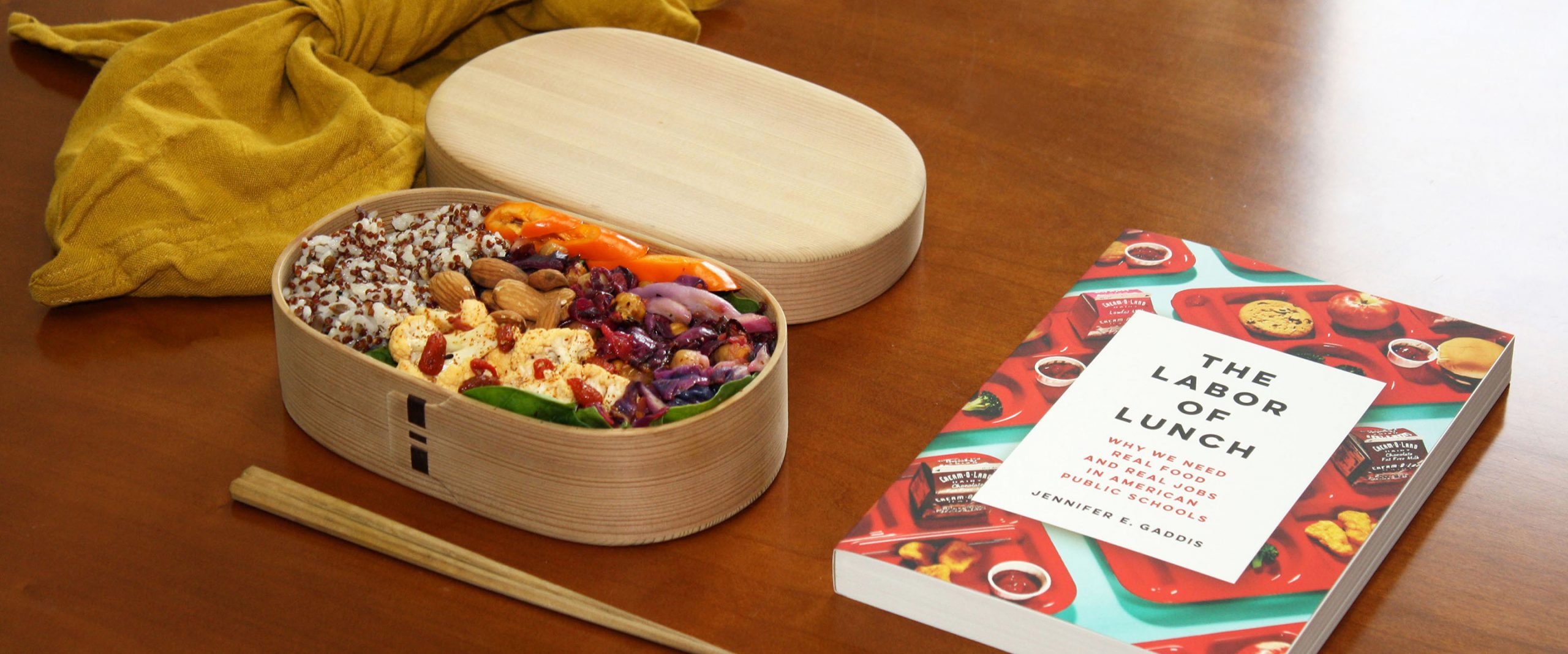

That she would one day author the book The Labor of Lunch: Why We Need Real Food and Real Jobs in American Public Schools and that this book would contribute to her eligibility for tenure at one of America's major research universities came as an unexpected turn in Gaddis' career path. Though she earned her undergraduate degree in Materials Science and Engineering, she discovered early on that this field of study was not the right fit for her.

"I probably knew by my sophomore year that I didn't necessarily want to be an engineer because a lot of the things that I was interested in seemed like social and political issues with respect to sustainability, versus things that were purely technological," says Gaddis. She is honest about the fact that she stayed in the program because she received a full scholarship and was concerned about taking on student debt were she to transfer to another program.

Dr. Jennifer Gaddis pictured on campus at UWM in Madison, Wisconsin. Gaddis serves as faculty advisor for Slow Food UW, a student organization that promotes and models an alternative food system.

Upon graduating, Gaddis applied for several interdisciplinary graduate degree programs and eventually enrolled at Yale University, where a variety of people and experiences sparked her interest in food systems as a lens for studying the intersection between community members and their environment. Her direction forward, however, remained unclear.

Gaddis explains, "My first couple years of grad school were hard for me because I started my PhD when I was twenty-three and I was transitioning fields from engineering to I-wasn't-really-sure-what, and everyone else in my cohort already had a master's degree and seemed really focused, so I dealt with a lot of feelings of imposter syndrome."

With the guidance of an advisor, Gaddis began to conduct research on the topic that would eventually become the focus of her first book and the courses that she would teach as assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Yet even as she approached the end of her PhD program, she was not committed to pursuing a position in academia.

"The academic jobs world can be really opaque and unless you have good mentors who are explaining unwritten stuff to you, it can be hard to figure out," says Gaddis. "I didn't have much of a concept of what an academic job even really meant when I was applying for jobs."

Because of Gaddis' particular study focus and work experiences during her PhD program, she was well-positioned to take on a professional role with a non-profit or government agency. However, "I really liked the idea of having a lot of freedom in terms of directing what my research questions would be." Her decision to work with a university ultimately was founded on the feeling that she would have more agency for her research without the pressure of prioritizing projects to satisfy a specific organization or grant funder.

Gaddis began work at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in August of 2014. As an assistant professor, she does much more than just lecturing to students. Less than half of her time - roughly forty percent of her workweek - is devoted to teaching two courses in the Department of Civil Society and Community Studies. Another forty percent of her working hours are spent on research projects. The final twenty percent of Gaddis' schedule is allocated to what she refers to as "a murky category called 'service.'" During the time put aside for this kind of work, she acts in service to her profession in a variety of ways, such as advising graduate students or serving on related scholarly committees. Part of her service hours are allotted to her duties as the faculty advisor for Slow Food UW, a student-led body that organizes food-centric activities on campus and within the local community.

Gaddis argues that the wellbeing of students depends upon the wellbeing of the people who produce and prepare the food

Gaddis' PhD and professional research focuses largely on the American National School Lunch Program. She originally felt compelled to study this subject matter and to later publish The Labor of Lunch (which looks at the evolution of the program since it was created in 1946) specifically because of the program's potential to affect the public at large.

"Our National School Lunch Program feeds about thirty million kids every day and we spend about fourteen billion dollars in federal funding on it annually. It's something that exists in roughly a hundred thousand different schools across the country - ninety-five percent of our public schools," explains Gaddis.

UWM student murals in the Slow Food UW dining space reflect the people and importance of access to organic food.

"A significant proportion of kids are getting up to two-thirds of their daily nutritional intake from this program. We're employing 420,000 or so workers in the school food program. We're indirectly impacting people across the food chain with the kind of choices that we're making about procurement. It just felt to me that it could be a pretty big leverage point for changing what our food systems look like. I really liked that it wasn't about starting something new and scaling up across the country. The infrastructure already exists, so it's more about shifting our priorities in terms of how we envision this program."

While the national conversation about school food has often centered on the nutritional quality of the meals available to elementary and high school students, Gaddis argues that the wellbeing of students depends upon the wellbeing of the people who produce and prepare the food. These individuals predominantly identify as women and as people of color, and they are rarely treated with the respect and gratitude that they deserve for their contributions to nourishing millions of children every day.

the American public must be willing to make a greater emotional and economic investment in the school food program

In her book, Gaddis advocates for increased wages and better benefits for school cafeteria workers. She also points out that one way to improve both job quality for these workers and the nutritional quality of the food for students is to increase the amount of from-scratch cooking in school cafeteria kitchens. To make these changes, however, the American public must be willing to make a greater emotional and economic investment in the school food program.

"According to the most recent numbers [from 2019], about three-quarters of the students who participate in the National School Lunch Program receive free or reduced-price meals based on their household income," says Gaddis.

what it really communicates is that school meals are for some people and not others

"It's really important to recognize that there are about fifty million kids in the U.S. that actually have access to the National School Lunch Program (meaning that their school participates and they could eat these meals if they wanted). Technically their meals, too, are subsidized by the government (just to a lesser amount), but the majority of upper middle-class and middle-class kids are opting out of the program. What that means is that in a lot of communities you see segregation in terms of who's lining up for the government-subsidized school meals. In a community like mine in Madison, Wisconsin it's a lot of Black and Brown kids who are lining up for school lunches and a lot of the White kids are bringing from home or purchasing food from the a la carte line."

As a result, Gaddis claims, "The way in which students access the food that they're eating for lunch becomes a symbolic divider not only of class, but, in a lot of cases, race as well. I and many other people advocate for a universal free school food program because right now we have this model where we're sorting kids into different categories based on their families' economic status and I think what it really communicates is that school meals are for some people and not others. I think that it really decreases our collective political will to invest in making this program the best it could be for everyone."

Recent school closures due to the pandemic have added a greater sense of urgency to Gaddis' work as a scholarly activist. "The intersection of food and care has been amplified by our current moment of crisis," she observes.

During the pandemic, UWM uses mini robots to shuttle around campus and deliver food to students. At the Slow Food Café, meals are currently prepared and packaged for pickup only.

While the publication of The Labor of Lunch in 2019 was a key professional milestone for Gaddis, she claims that the "public scholarship" work that has followed - in which she has been invited to share her research findings with a wider audience through other platforms, such as op-eds and podcasts, and through consultations with policy makers - has been "the most rewarding part of my job so far." She continues to pursue this work remotely, knowing that this moment presents a unique opportunity to change things for the better.

In order to respond to this crisis and move towards a more equitable and sustainable model of food production and consumption, Gaddis asserts, "We need to be very careful and strategic about trying to use our public food dollars in a way that helps to end racial and economic exploitation in our food system."

Elena Valeriote is a writer who specializes in stories about food that demonstrate our collective power to create a more equitable and sustainable food system. With experience at many different links in the supply chain ranging from production to distribution, as well as hospitality, food policy, and beyond, Elena's holistic approach to food writing draws attention to the value of the land, plants, animals, and people that nourish us every day. You can stay updated on her latest work by following her on Instagram at @elenavaleriote.

Roxsand King is a freelance photographer based in Chicago. Photography has been her creative passage to further connect with the world. Having a professional background in interior design brings a unique approach to her work. Roxsand credits the love of photography to her grandfather; he always kept a camera nearby, and she does the same. To see more of Roxsand's work, visit www.rorokiimages.com, and follow her on Instagram @rorokiimages.